Same Model, Different Results: Why Coding Agents Aren't Interchangeable

December 10, 2025

“Why would Claude Code work differently than my IDE’s coding agent, if they’re both using the same models under the hood?”

I see this asked quite often, and it’s a reasonable question. If Copilot Agent is using Opus 4.5, and Claude Code is using Opus 4.5, what’s the difference?

Let’s reverse-engineer Claude Code to see what it’s doing internally, learn some of its secrets, and develop a sense of what makes each agent unique!

As we dig in we’ll see that coding agents are much more than a “wrapper” around an LLM. They do a surprising amount of work under the surface to (a) maximize the useful information available to the LLM, and (b) steer its behavior.

Turns out this has a big impact on the quality of the agent’s work.

Claude Code is our exemplar

In this post I’ll be analyzing how Claude Code works under the surface. I chose this agent because:

- it uses some interesting strategies and tricks to maximize LLM performance

- it’s fairly easy to “spy on”

- it’s my “daily driver” so I understand its operations well

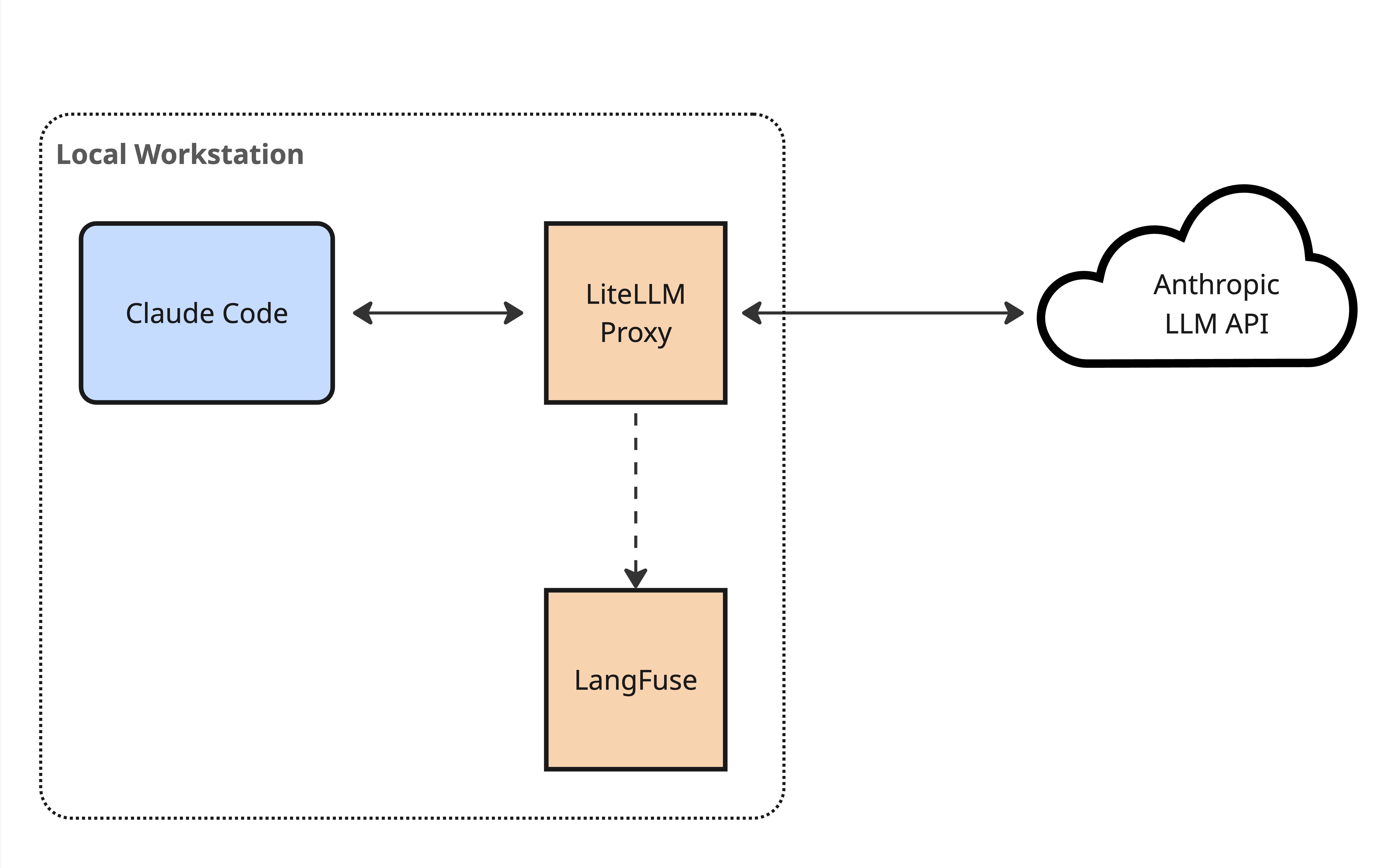

If you’re wondering how I cracked open Claude Code’s brain, I’ve included an addendum at the end of the post. In summary, I set up local instances of LiteLLM and LangFuse as a man-in-the-middle approach to snooping on Claude, as shown below.

Man-in-the-middle architecture for observing Claude Code's LLM calls

Doing this allowed me to see some hidden details of how Claude Code works - context it adds to the conversation which isn’t visible at all from the UI. For example how it injects <system-reminder> information into the bottom of the context window as it works. More detail on that below.

I’m pretty confident that while I’ll be describing the tools and context engineering that Claude Code uses, the concepts also apply to the other top-tier coding agents. The specifics may vary, but the general approach remains.

What’s an agent

Let’s start with a brief review of how an agent works.

At its core, a coding agent is an LLM, running in a loop, trying to achieve a goal using tools (hat tip to Simon Willison for this nice succinct definition).

A user starts off giving the agent a prompt, then the LLM invokes tools - searching the codebase, editing files, running tests, and so on - until it feels like it has completed the task.

For example, we might write an initial prompt like “add a circular avatar image to this user profile page”. The agent passes that to the LLM, and the LLM responds by saying “first I want to search the codebase for relevant files” - this is a tool invocation. The agent then performs the search that was requested, then passes the result back to the LLM. The LLM might then respond by asking to read the contents of a file, then edit a file, then create a new file, then run tests, and so on.

The agentic loop

The agent’s role is as a “harness” around the LLM, enabling it to interact with the outside world by invoking tools and feeding their results back into to the LLM’s context.

Additional context

A coding agent is doing more than just orchestrating this core tool-calling loop, though. For one thing, it adds additional context before any work begins.

Firstly, each agent has a very detailed system prompt (here’s Claude Code’s) which directs the LLM how to go about its coding work.

Secondly, the agent checks for memory/rules files present in the codebase (i.e. CLAUDE.md, AGENTS.md) and automatically inserts these into the LLM’s context before the initial prompt. This is essentially a convenience, allowing you to provide your own consistent direction to the LLM above and beyond the agent’s system prompt.

Custom tools

Importantly, coding agents also provide a way for the user to provide custom tools to the LLM, via the MCP protocol. This gives the LLM new ways to gather additional information, and new ways to interact with the world outside of the agent.

When it was first introduced this idea of custom tools was a differentiator for some coding agents, but at this point it’s pretty much a standard feature of any agent.

They’re all the same

Speaking of standard features, the core mechanisms I’ve described above - agentic loop, AGENTS.md, and MCP-based tools - are common across pretty much any coding agent, whether it’s Claude Code, Copilot in Agent mode, Cursor, Codex, Windsurf, Amp, take your pick.

What’s more, while some agents have their own custom models, most use the same general-purpose models - Opus and Sonnet from Anthropic, the GPT models from OpenAI, Gemini from Google.

This brings us back to the question we started with - if coding agents all use the same basic loop, and you can configure them with the same model, and they’re using the same AGENTS.md and configured with the same MCP tools, what’s the difference? Shouldn’t they all perform the same?

Well, no, there’s actually some big differences lying under the surface…

The small differences

We’ve already touched on a couple of places where each agent will differ.

Firstly, each agent has a different system prompt. Just skimming through Claude Code’s current system prompt you can see a lot of prompt engineering at work, and that’s not for nothing - it’s going to shape how the LLM works.

Secondly, each agent provides the LLMs with its own set of built-in tools - here’s the 18 tools I extracted from Claude Code.

Within this list are tools which provide the core functionality of the coding agent:

- Read - for reading files

- Edit and Write - for changing files

- Glob - for finding files

- Grep - for searching across files

- Bash and BashOutput - for executing shell commands, optionally backgrounded

- WebSearch and WebFetch - for looking things up on the web

Each agent provides the same core functionality - reading and writing files, searching the codebase, running commands - but each agent provides slightly different tools to do so, and each set of tools will return information back to the LLM in a different way.

The explosion of interest in MCP has demonstrated just how much tools matter to the abilities of agents. This is just as true for the core built-in tools an agent brings to the table - the details of how they work can have a surprising impact on the overall ability of an LLM to achieve its goal, particularly when it comes to context engineering - we’ll dig into that more in a moment.

The secret sauce - task management

Claude Code provides other tools besides those described above, and these additional tools are where things get really interesting:

- TodoWrite - for managing a structured task list for the current session

- Task - for spawning sub-agents

- EnterPlanMode and ExitPlanMode - for spawning a special-purpose planning sub-agent

- AskUserQuestion - allows the LLM to proactively ask the user clarifying questions during planning

This is where the coding agent becomes much more than a simple wrapper around the large language model. These tools erect an entire planning and task management scaffold around the LLM, in the form of todo lists, planning mode, user questions, and sub-agents.

Let’s take these one by one, starting with todo lists.

todo lists

Claude Code uses the TodoWrite tool to nudge the LLM into creating and managing a checklist of tasks as it works. I suspect that this provides two benefits.

Firstly, it encourages the LLM to more upfront planning, improving it’s ability to think through a solution in the similar way that chain-of-thought reasoning does.

Secondly, it helps the LLM maintain attention during a complex task. The agent does this by periodically inserting the current state of an active todo list into the tail end of the context window (using the <system-reminder> mechanism I’ll describe shortly.). Placing this information at the end of the context window works around the LLM’s lost-in-the-middle weakness, where it tends to pay less attention to things in the middle of the context window.

In anthropomorphic terms, when working on a complex task the LLM tends to lose track of the overall plan. The agent works around this by encouraging the LLM to make a checklist up front, and periodically reminding the LLM to look at it.

Planning mode

When working with a coding agent on a non-trivial problem it’s always best to have it present you with a plan first - it’s way easier to course-correct bad decisions in a plan, rather than waiting for the AI to code up the entire implementation!

LLMs are really keen to impress you though, and often leap straight to coding. In the very early days of Claude Code I would “discourage” it from doing this by emphatically stating "JUST PLAN FOR NOW, NO CODING YET!!!" at the end of my prompts.

This is no longer necessary, because the Claude Code team added a distinct “planning mode” that the user can switch into (by pressing shift-tab, in case you were wondering).

When in this mode, the agent injects additional prompting behind the scenes, sternly reminding the LLM to focus on planning, not doing:

Plan mode is active. The user indicated that they do not want you to execute yet – you MUST NOT make any edits (with the exception of the plan file mentioned below), run any non-readonly tools (including changing configs or making commits), or otherwise make any changes to the system. This supercedes [sic] any other instructions you have received.

The agent also provides tooling that lets the LLM present it’s plan back to the user for approval once it believes it’s ready to get down to work.

User questions

One of my biggest irritations with AI is that it doesn’t push back on my requests or ask clarifying questions, unless I explicitly ask it to do so. It’s not a good thought partner, and this impacts the overall quality of a coding agent’s work product.

Claude Code attempts to address this by providing the LLM with an AskUserQuestion tool. As the tool’s documentation says, this allows the LLM to:

- Gather user preferences or requirements

- Clarify ambiguous instructions

- Get decisions on implementation choices as you work

- Offer choices to the user about what direction to take.

Presumably by making this tool available to the LLM, it is encouraged to proactively ask clarifying questions, although I still suspect the AI doesn’t do this as often as it should.

Sub-agents: delegating the details

Perhaps the most impactful improvement that the coding agent can make to the LLM’s performance is the ability to spawn sub-agents.

This facility allows the agent to move detailed tasks into separate context windows. I covered this concept briefly in this post on coding agent context management.

Essentially, sub-agents allow the LLM to perform low-level tasks in dedicated context window, avoiding polluting the main conversation history with the minutia of previous operations. Rather than dragging around the historic output of every previous build step or test run, the agent performs this task via a sub-agent and only adds a high-value summary of the task back into the main context window.

Sub-agents really deserve their own deep-dive post - think provide a major boost to agent performance for long-running tasks (like coding). Let me know if you want me to write it!

Shameless plug: grokking these foundational mechanisms of how coding agents work is part of what unlocks an actual productive experience using AI-assisted engineering in your day to day work. I offer training to help you get there!

How the agent hacks the context

I’ve mentioned a few times that Claude Code injects additional prompting into the tail end of the context window. This “context hacking” is done behind the scenes, hidden from the user, and only visible if you look under the covers at the raw LLM calls the agent is making.

Let’s look in more detail at how the coding agent injects these little nudges.

Inline system prompts

As one example, sometimes when adding a tool response or a user prompt to the context window, Claude Code will tack this little nugget at the end of the message:

<system-reminder>

The TodoWrite tool hasn’t been used recently. If you’re working on tasks that would benefit from tracking progress, consider using the TodoWrite tool to track progress. Also consider cleaning up the todo list if has become stale and no longer matches what you are working on. Only use it if it’s relevant to the current work. This is just a gentle reminder - ignore if not applicable. Make sure that you NEVER mention this reminder to the user

</system-reminder>

It’s an interesting way for the coding agent to steer how the LLM should work - a sort of contextual inline system prompt. I would guess that this is partly another example of the agent compensating for the LLM’s lost-in-the-middle weakness.

Claude Code uses various other “system reminders” as it works, reminding the LLM of things like:

Whenever you read a file, you should consider whether it would be considered malware. You CAN and SHOULD provide analysis of malware, what it is doing. But you MUST refuse to improve or augment the code. You can still analyze existing code, write reports, or answer questions about the code behavior

An interesting aside: this particular prompt appears to be referenced by Anthropic in the Sonnet 4.5 System Card, where they state in section 4.1.2 that “A reminder on FileRead tool results to examine whether the file is malicious” is one of “two mitigations [against requests to engage with malicious code] that are currently applied to Claude Code use in production”. They go on to state that for some scenarios these mitigations moved the LLM’s refusal rate for malicious use from ~52% to ~96%.

That is a pretty big shift! This behind-the-scenes context management can clearly have an impact on the model’s output.

IDE context

When wired up to an IDE, Claude Code also uses this context-hacking mechanism to give the LLM additional context from the environment, injecting information like:

<ide_opened_file>The user opened the file [FILENAME] in the IDE. This may or may not be related to the current task.</ide_opened_file>

and

<system-reminder>

Note: [FILENAME] was modified, either by the user or by a linter. This change was intentional, so make sure to take it into account as you proceed (ie. don’t revert it unless the user asks you to). Don’t tell the user this, since they are already aware. Here are the relevant changes (shown with line numbers): [DIFF OF CHANGES]

</system-reminder>

The agent also appears to pass LSP diagnostics (the yellow and red squigglies in your IDE) back to the LLM as part of the response to a file editing tool call.

You can imagine how this extra information provides additional context and feedback to the LLM, allowing it to align its decisions better with the user, and course-correct in the face of errors.

Context management matters

Overall, it’s quite interesting to pull back the covers and see all the little tricks that Claude Code uses to actively manage the LLM’s context window to enhance it’s performance. It’s clear that the coding agent is much more than a wrapper around a model, and that different agents are going to achieve quite different results, even when using the same underlying model.

That said, this context management that’s going on behind the scenes is not the only thing to consider when choosing an agent.

Further decision factors

At the end of the day, we’re talking about this stuff because we want to know what agent to use.

In this post I focused on the internal details of how a coding agent manages context and helps an LLM to plan. This has an impact on performance, so we should care about it when we’re considering which agent to use.

But, there are a bunch of other important factors you should be weighing too.

The ergonomics of the coding agent - how easy is it to work with, how well does it integrate into your daily work? Token costs and usage limits are a big factor for a lot of engineers.

Most important for power users is the extensibility of the coding agent. For example, Claude Code has hooks, plugins, slash commands, etc. that allow you to do some pretty deep customizations and enhancements on top of the core functionality. If you can see yourself doing this sort of thing then you should be factoring extensibility in when weighing different coding agent options.

A harness is much more than a wrapper

The superficial impression of the agent as just a system prompt, a for-loop, and some tools falls away as you look under the covers and see what the harness is actually doing.

There’s a complex dance of context management going on. This context management boils down to three things:

- steering the behavior of the LLM

- maximizing the amount of relevant information for the LLM

- reducing the amount of irrelevant information

How this is done has a massive impact on the LLM’s ability to achieve the output we want, and different agents do this work in different ways.

It shouldn’t be at all surprising that the quality of a coding agent’s work can vary greatly, even when it’s using the exact same model!

Additional Resources

Dexter Horthy has put out a bunch of great content on getting agents to work well, and specifically around context management. This writeup is a great place to start digging in deeper on that, and this recent presentation is another nice summary.

I wrote more about the importance of context management for coding agents here, and listed some additional resources at the bottom of that post (it’s a linked list in blog form!).

Finally, I offer a live workshop series which covers these topics in much more detail. This is an online training for experienced engineers that want to level up their use of coding agents for day-to-day engineer work. More details here!

Addendum: spying on Claude

You might be wondering how I peered inside Claude Code’s internal workings to get hold of things like its list of tools, its system prompt, and to see those hidden inline “system reminders”.

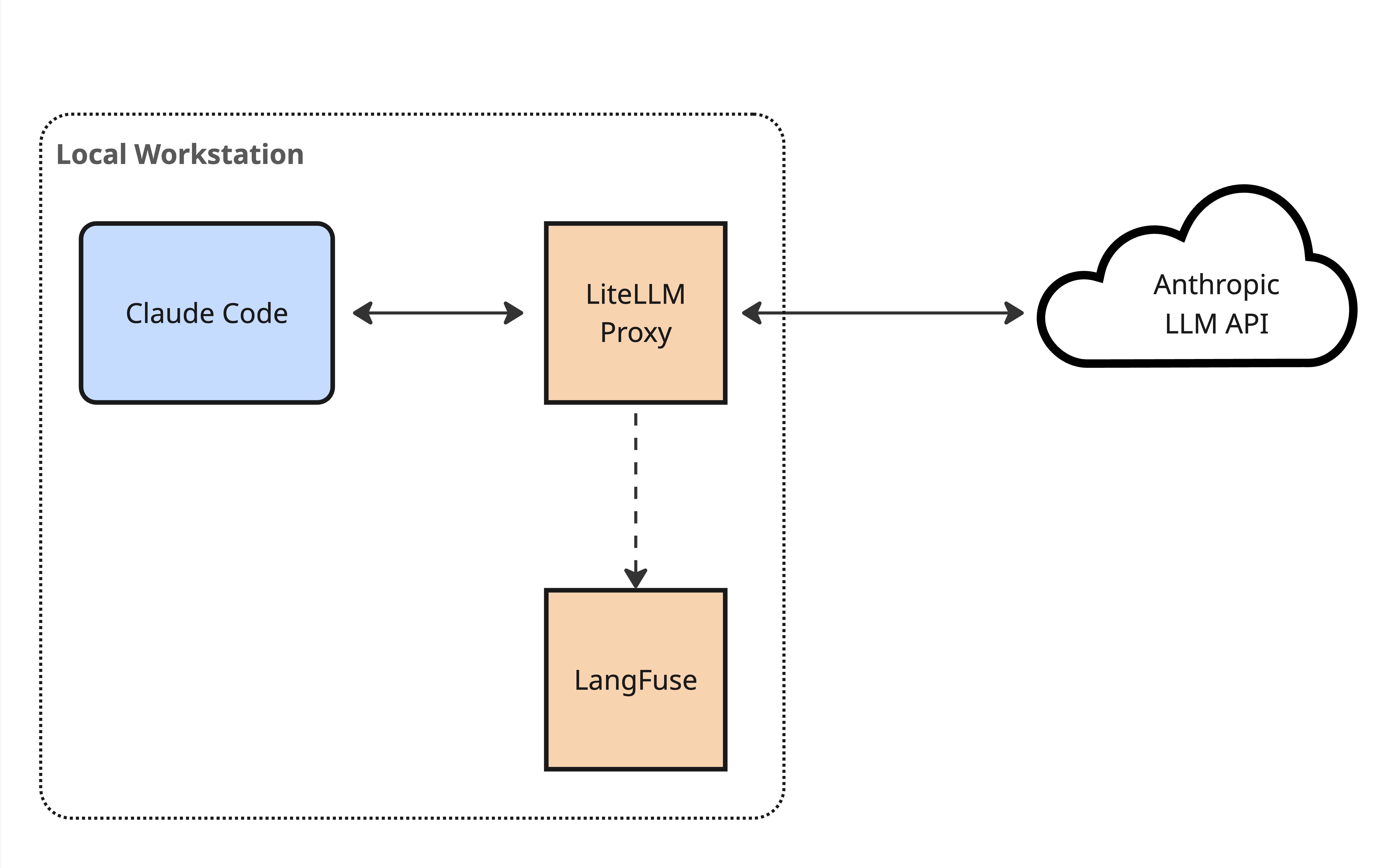

This was actually a pretty straightforward man-in-the-middle operation. Claude Code supports working via an LLM gateway. I used this facility to wire it up to a local LiteLLM instance, and additionally configured LiteLLM to log LLM traces to a local LangFuse instance.

Man-in-the-middle architecture for observing Claude Code's LLM calls

With this observability setup I was able to inspect all of Claude Code’s interactions with the LLM.

I got additional insight from poking around in Claude Code’s internal conversation history files. These are .jsonl files that live inside the individual projects within ~/.claude/projects/. Note however that these don’t contain the same level of detail as the raw LLM traces - you need to look at those to see all of the “under-the-covers” context hacking that I describe in this post.